Season Of The Witch

Loose, peppery, brief encounters while wrenching giddy acts of God out of musical instruments.

“The music on this record was performed spontaneously by the personnel as listed. The horns were added later as an afterthought.” - Al Kooper

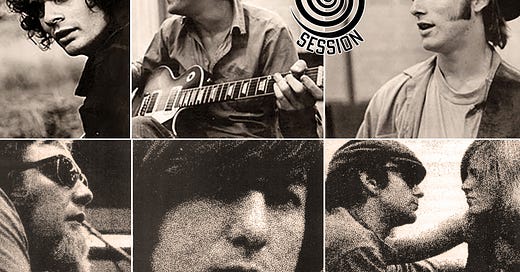

Bloomfield, Kooper, Stills - ‘Super Session’ (1968)

They don’t make rock and roll records like this anymore.

No, I mean it... they really don’t make records like this anymore. Sure, there are plenty of jazz records like it, but not rock and roll.

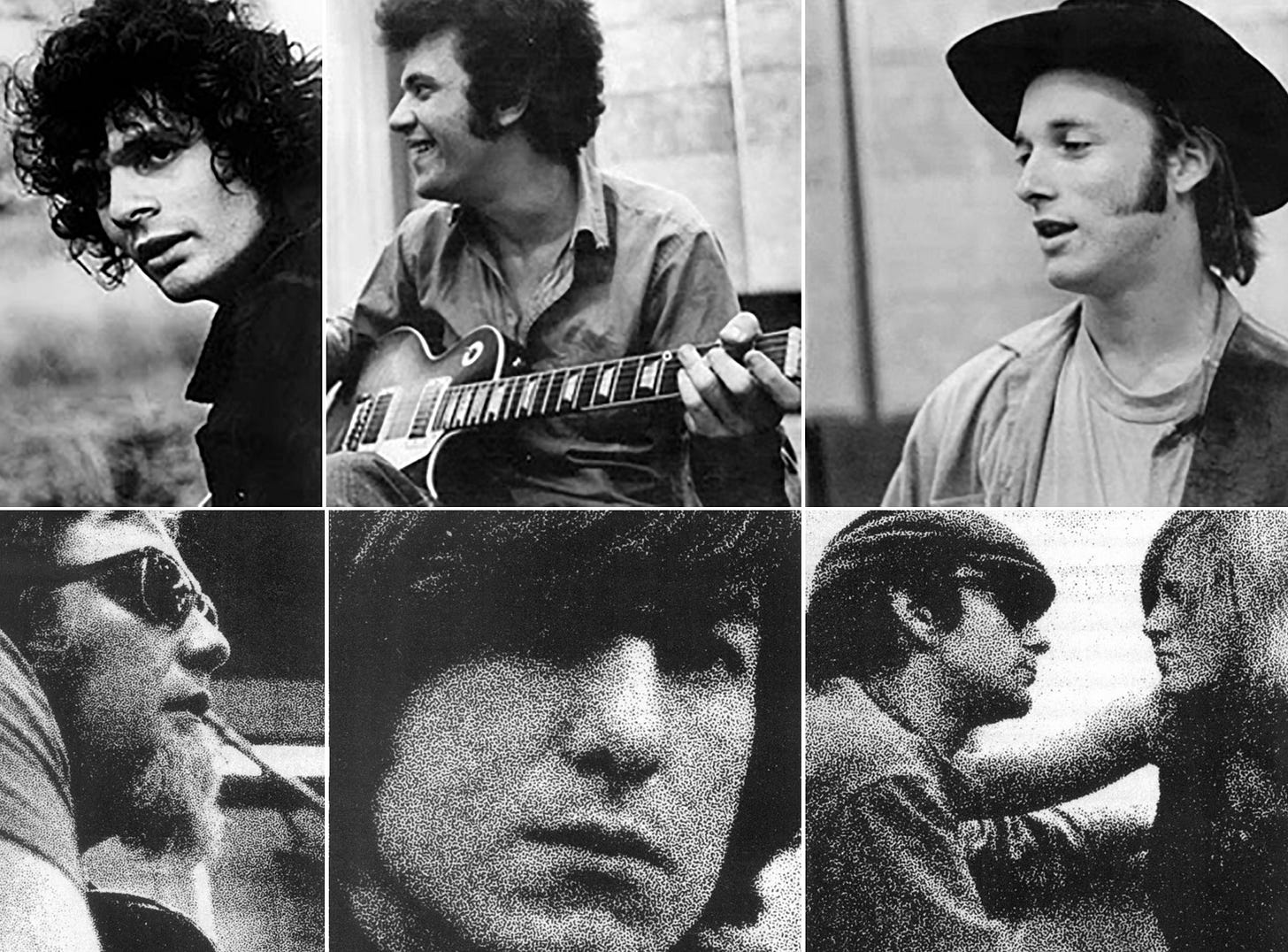

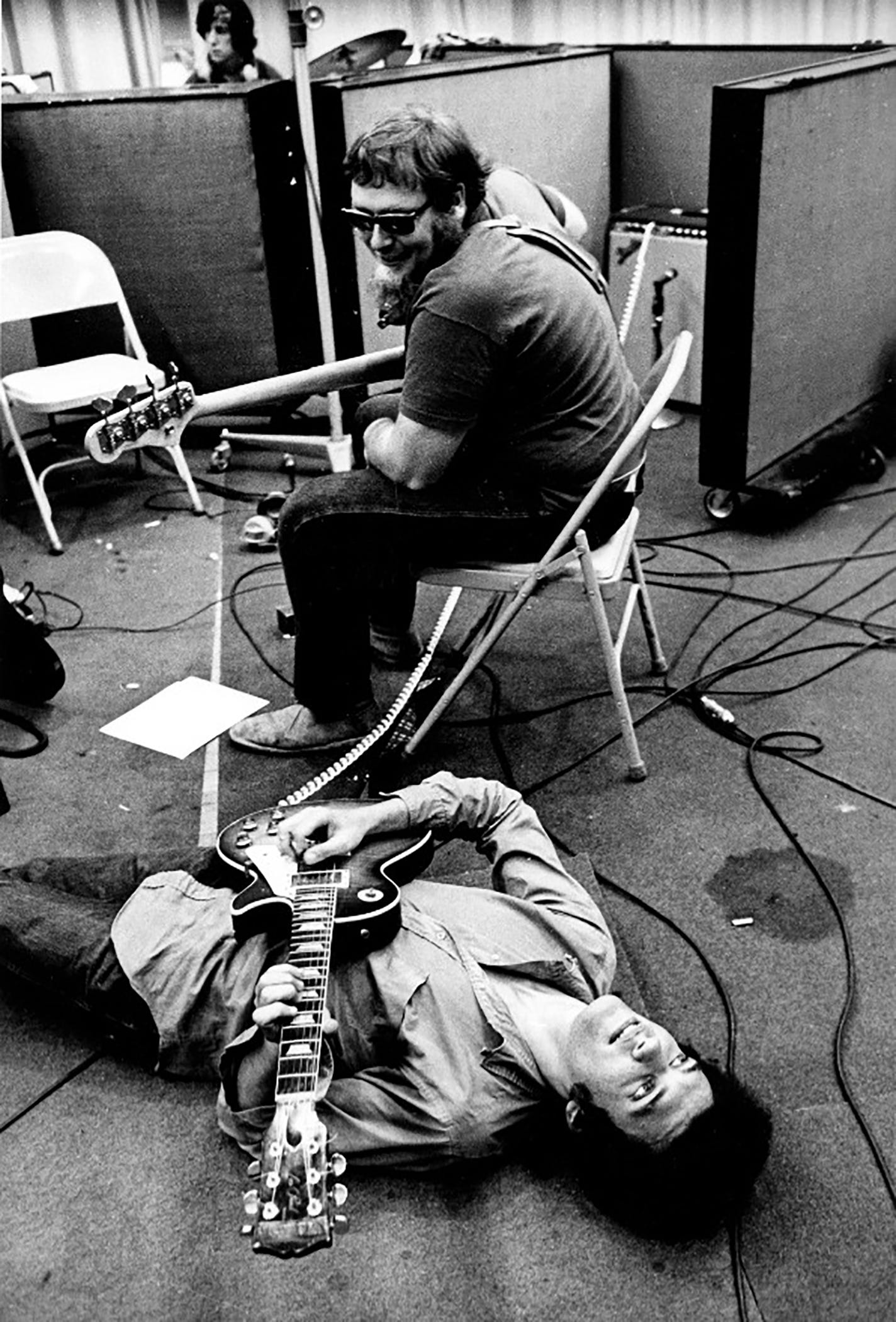

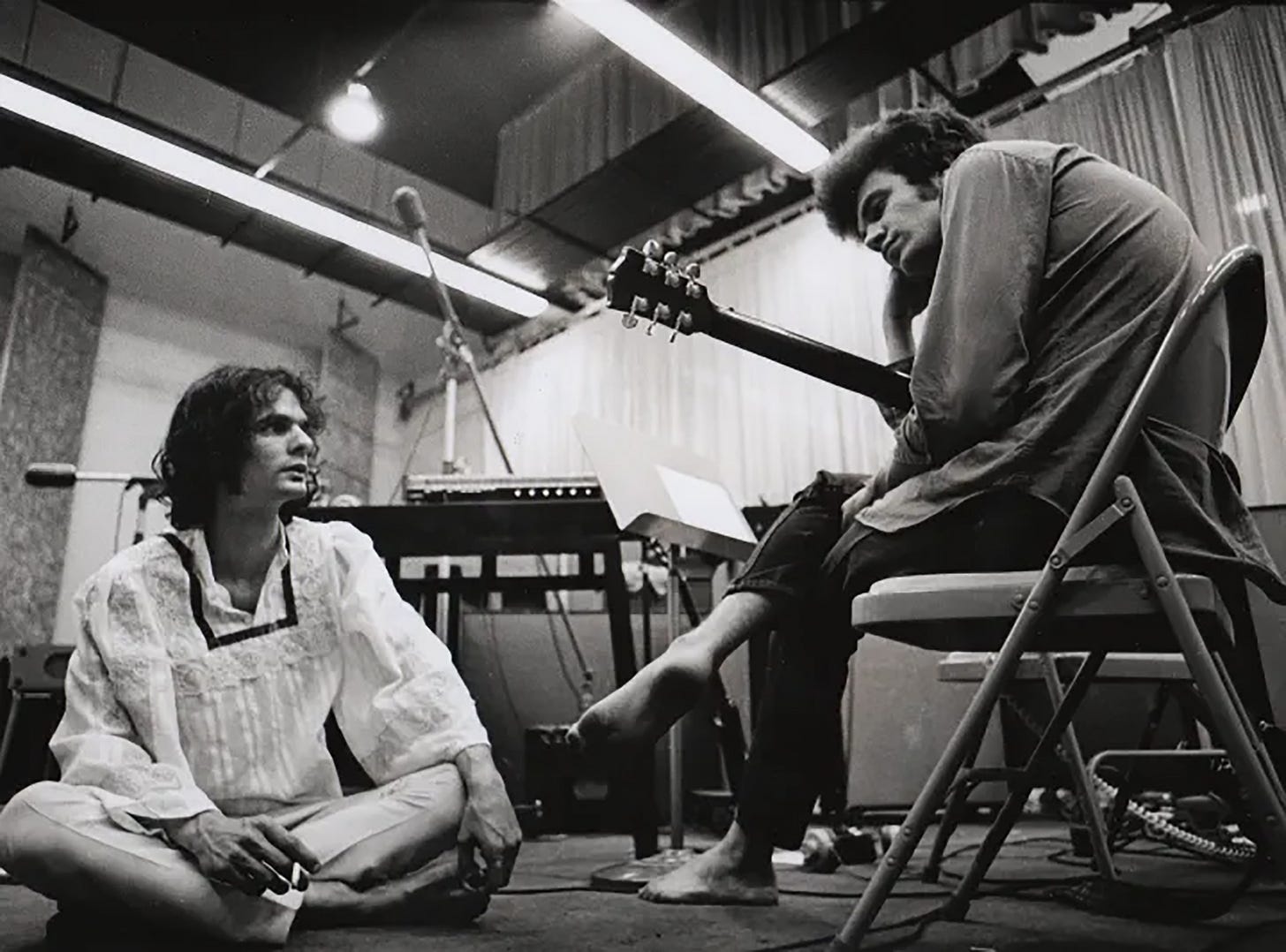

Imagine the scene—a handful of musicians from various bands, all highly respected and famous, rent a studio, get together late at night, and jam. Better yet, they hit “Record” and captured the whole bloody session on tape. That’s exactly what happened over two days back in May 1968 when keyboardist Al Kooper (The Blues Project and Blood, Sweat, & Tears) called his guitarist friend Mike Bloomfield (Butterfield Blues Band and The Electric Flag) and asked if he wanted to jam and see what comes out of the session. Bloomfield agreed and said he would bring his friend and drummer, “Fast” Eddie Hoh. Meanwhile, Kooper invited other ex-Electric Flag members, pianist Barry Goldberg and bassist Harvey Brooks, to round out the set.

“The best things happen after hours, by accident, while the cat’s away, when the moon goes behind a cloud and there’s no one else around; certainly the best music in America is made after twelve, deep in the rock and roll dungeons, little clubs in New York and California, when whoever’s in town and feeling restless, a bass player from one band and a drummer from another, a couple of guitar players and piano players from a couple of others, rock and roll strays, they get together and jam, sometimes they collide, more often than not they tempt each other to take more and more risks, always they discover something they’d perhaps had in mind but couldn’t quite bring home before, they dare and thrill each other, and, because there’s nothing to lose that’s not best done without, and there’s no one to please but themselves…”1

Kooper and Bloomfield had crossed paths a few years earlier when they were part of the electrified recording sessions for Bob Dylan’s ‘Highway 61 Revisited.’ However, by May 1968, musically, both were at a crossroads, having been kicked out of the bands they had formed. They already had an established connection and musical bond, and on a whim, Kooper called Bloomfield and asked if he wanted to get together and jam. Bloomfield agreed, and Kooper booked a studio for two days. On the first day, the musicians came together later in the evening for what would eventually become an extensive and productive nine-hour jam session.

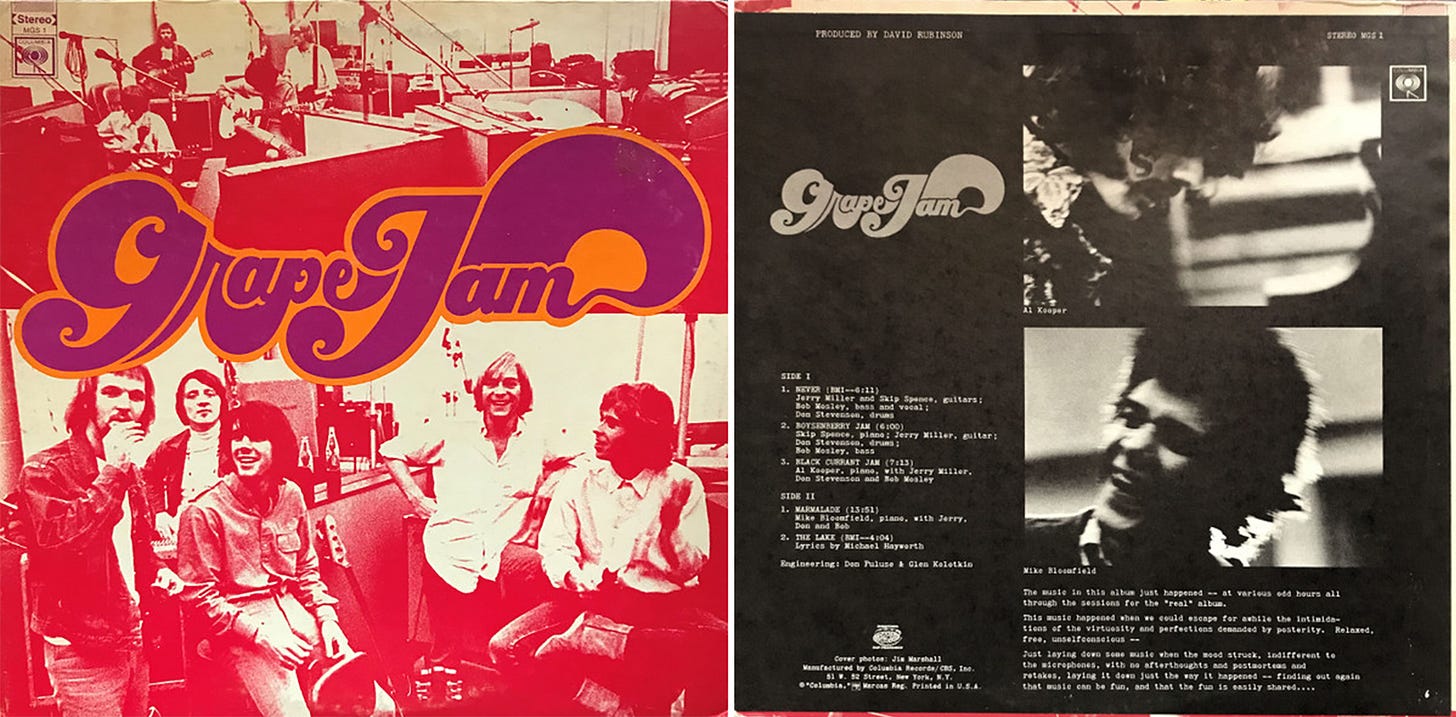

A few months earlier, in January and February 1968, the great San Francisco band Moby Grape recorded a separate jam record that was included in the release of their second album, ‘Wow,’ which came out in April of that year. This jam session was aptly named ‘Grape Jam.’2 Notably, Bloomfield and Kooper were invited to contribute and appear on two separate tracks. A precursor to the vibe of ‘Super Session,’ the back cover of ‘Grape Jam’ features notes that reflect this collaborative spirit…

“The music in this album just happened – at various odd hours all through the sessions for the “real” album. This music happened when we could escape for a while the intimidations of the virtuosity and perfectionism demanded by posterity. Relaxed, free, unselfconscious – Just laying down some music when the mood struck, indifferent to the microphones, with no afterthoughts and postmortems and retakes, laying it down just the way it happened –finding out again that music can be fun, and that the fun is easily shared…”

While the ‘Grape Jam’ album embraced its loose, relaxed, late-night, free-form vibe. Kooper had some structure in mind for his jam session. Still, nothing was written in advance; there was no preconceived idea of what they would play—the idea was to come into the studio, hash out some original jams, and then try their hand at a couple of familiar numbers and see where the music would lead them.

The recordings made during this first session comprise Side A of what would later be known as the 'Super Session' album, released just two months later in July 1968.

The record's first side draws heavily from Bloomfield's passion for Chicago blues, immersing us in spontaneous white boy blues jams. The LP opens with the Bloomfield/Kooper composition, ‘Albert’s Shuffle,’ before transitioning into the utterly magnificent version of Jerry Ragovoy & Mort Shuman’s ‘Stop,' which was originally recorded by Howard Tate a year earlier. Bloomfield’s guitar absolutely rips, starting with a funky rhythm before letting loose with a piercing solo that squeals and screams. Kooper and Goldberg’s organ and piano whistle and soar to tremendous heights. Underneath it all, Hoh and Brooks groovily keep the time and a steady rhythm to the jam. All musicians are in full sync, and at its peak, during Kooper's otherworldly organ solo, they are totally cookin'.

Unfortunately, the album transitions into its least impressive track, a lackluster and uninspired cover of Curtis Mayfield’s ‘Man’s Temptation.’ The lyrics are outdated and downright cringey. While Mayfield and The Impressions infused the original with raw, soulful emotion, Kooper’s vocals fall short, making it the album's one throwaway track.

It is quickly overshadowed, however, by Side A’s creative zenith, 'His Holy Modal Majesty,' a nine-minute homage to John Coltrane. Kooper’s playing of the Ondioline produces psychedelic, baroque, and almost Eastern melodies that swirl, spiral, and wispily drift & float like smoke. You can just about smell the aroma of incense, cigarettes, weed, and whiskey, and feel the warm glow of a Moroccan lantern as their sonic love supreme fills the room. It is a breathtaking track that easily stands out as one of Kooper’s most imaginative and inventive performances ever recorded.

The first side concludes with another Kooper/Bloomfield original Albert King-inspired blues jam titled, ‘Really.’ Clocking in at 28.5 minutes, despite one misstep, it’s an astonishing side of music.

However, as is often the case with making art, not everything went exactly to plan…

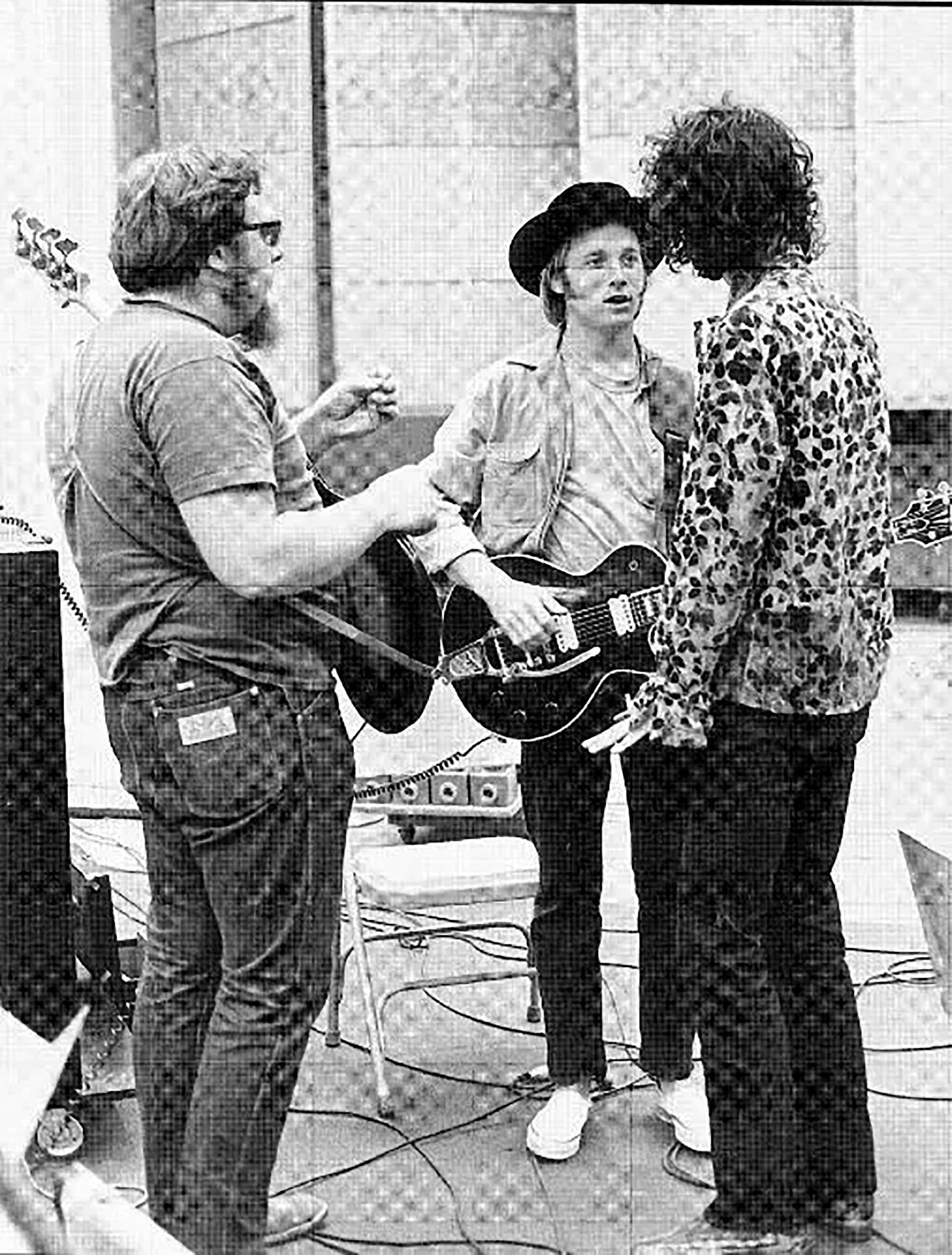

The next day, as fate would have it, Bloomfield, the “incurable insomniac,” unexpectedly split back to the Bay Area, leaving Kooper scrambling. Kooper reached out to three West Coast guitarists, Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead, Randy California of Spirit, and Stephen Stills, asking if they were interested in a recorded jam session. Fortunately, Stills was on a break from his band, Buffalo Springfield, and agreed to join the session for the second day.

Similar to the day before, but even more spontaneous due to Bloomfield’s hasty departure, there was even less to build on as the musicians hadn’t jammed with each other before. Nevertheless, being creative professionals, they got down to business, had fun, and hit “Record” for the second time.

Stephen Stills brought with him an entirely different approach to music. Gone was Bloomfield’s Chicago blues, now replaced with Stills’ hippie, Californian jingle-jangle Cosmic Country Folk Rock. This makes Side B much more song-focused and arguably more accessible for the casual listener.

Opening with the country’esque jangle fuzz rendition of the Dylan number, ‘It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry,’ from the get-go, it’s obvious Side B is headed in an entirely different direction. Stills's gorgeous, countrified guitar solo with Brooks’ fuzz bass, Kooper’s distorted organ, and Hoh’s outstanding drumming make for a fantastic, rippin’, and unforgettable take of the song.

It then segues into Side B’s extended track, a cover of Donovan’s ‘Season Of The Witch.’ Back in 1966, drummer Eddie Hoh contributed as a session musician on Donovan’s legendary ‘Sunshine Superman’ LP, which includes the original version of ‘Season Of The Witch’. This may give some insight into the choice of this particular song. On the Super Session version of ‘Season Of The Witch,’ Stills, the guitar gunslinger, saturates his guitar with wah-wah and effortlessly plucks out one delicious, liquidy, funky guitar riff after another. Hoh’s drumming is, yet again, exceptional throughout, and just like in ‘Stop,’ when Kooper unleashes his organ solo, the band is in full-throttle beast mode. The afterthought of the horns is a stroke of genius, elevating what was already a very groovy but raw jam session into a finely tuned and polished song.

While Kooper manages the vocals competently, I have to wonder why Stephen Stills is not given the opportunity to sing, especially on this track where his voice would have been outstanding. The only plausible reason I have heard is legal complications with record labels, as Stills was still under contract with Atlantic Records, and they were recording this album for Columbia. Nevertheless, the band absolutely killed it, and it is arguably the most popular track on the record.

The album transitions into another standout track, the hard-rockin' flanger and phaser-soaked cover of Willie Cobb’s ‘You Don’t Love Me.’ Yet again, it’s a moment where Stills’ vocals would have taken the song to even greater heights. This isn’t meant to undermine Kooper’s singing; rather, Stills, with his experience in Buffalo Springfield, possesses superior tone, harmony, and vocal range. Thus, it’s no surprise that he would soon be invited to collaborate with David Crosby and Graham Nash, forming the iconic supergroup Crosby, Stills & Nash.

The album concludes with the Harvey Brooks original, ‘Harvey’s Tune,’ a bluesy, jazz number that was also given new life thanks to Kooper's later addition of horns.

To the amazement of all involved, ‘Super Session’ was an unexpected hit, ultimately achieving gold record status and peaking at #12 on the Billboard 200, where it remained for an impressive 37 weeks. Although Stills would later find even greater success with CSN and CSN&Y, ‘Super Session' was Bloomfield and Kooper’s most successful record of their career.3

Following the unexpected success of the album, Kooper and Bloomfield played three shows at the Fillmore in San Francisco in late September 1968 and recorded it for a live double LP. True to form, Bloomfield made it through the first two dates, but the “incurable insomniac” was ultimately hospitalized on the third day, and Kooper, left scrambling yet again, appealed to the Bay Area music community, and Elvin Bishop, Steve Miller, and a young, unknown Carlos Santana came to the rescue.4

The album was released as The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper, featuring cover art painted by Norman Rockwell. Later that year, Kooper would record another jam session featuring the then young, remarkably talented fifteen-year-old Shuggie Otis, simply titled Kooper Session - Al Kooper Introduces Shuggie Otis.

In today’s digital landscape of overly produced, excessive autotuned perfection, artists and bands that frequently sound very similar to one another, uninspired and stale award ceremonies, and the looming prospect of AI-generated music, an album like Bloomfield, Kooper, Stills-‘Super Session’ is a refreshing and rewarding spin. It literally has the artist’s hands all over it, making it totally heartfelt and completely honest music. It may be a relic of the past, but it was created entirely by creative, inspired, talented human beings in just two late-night Super Sessions.

Yeah, they don't make records like this anymore, but fucking hell, I wish they did.

Liner notes on the back cover of ‘Super Session’ written by Michael Thomas

Hey, I like Led Zeppelin, but if more proof were ever needed to highlight how much they ripped other artists off—compare Moby Grape’s ‘Never’ (recorded in 1968) to Zeppelin’s ‘Since I’ve Been Loving You’ (recorded in 1970). It’s as blatant as their rip-off of Willie Dixon & Muddy Waters ‘You Need Love.’

Side note- I have two copies of ‘Super Session,’ stereo and SQ quadrophonic. Since I don’t have a quadraphonic setup, listening to the latter on my stereo feels like experiencing a completely different album. The mix varies significantly, and my turntable’s needle reveals guitar parts that I either overlooked or simply can’t hear in the stereo version.

Steve Miller doesn’t appear on the live album due to contractual reasons.

This is so well-written that I'm going to have to keep revisiting it. While I'm familiar with some of the "participants", I don't think I'd heard much of this album, other than a passing comment. The genre is way up my street, so this is exactly what I needed to, if you'll pardon the pun, beat the Monday blues. Thank you!

Great album of my youth for sure! Well written.